.png)

Having lived in South Africa for six years, I wanted to see from the air a problem I had often thought about: a problem proposed by the end of apartheid, when black people had to enter into and possess a world that white people believed they had created.

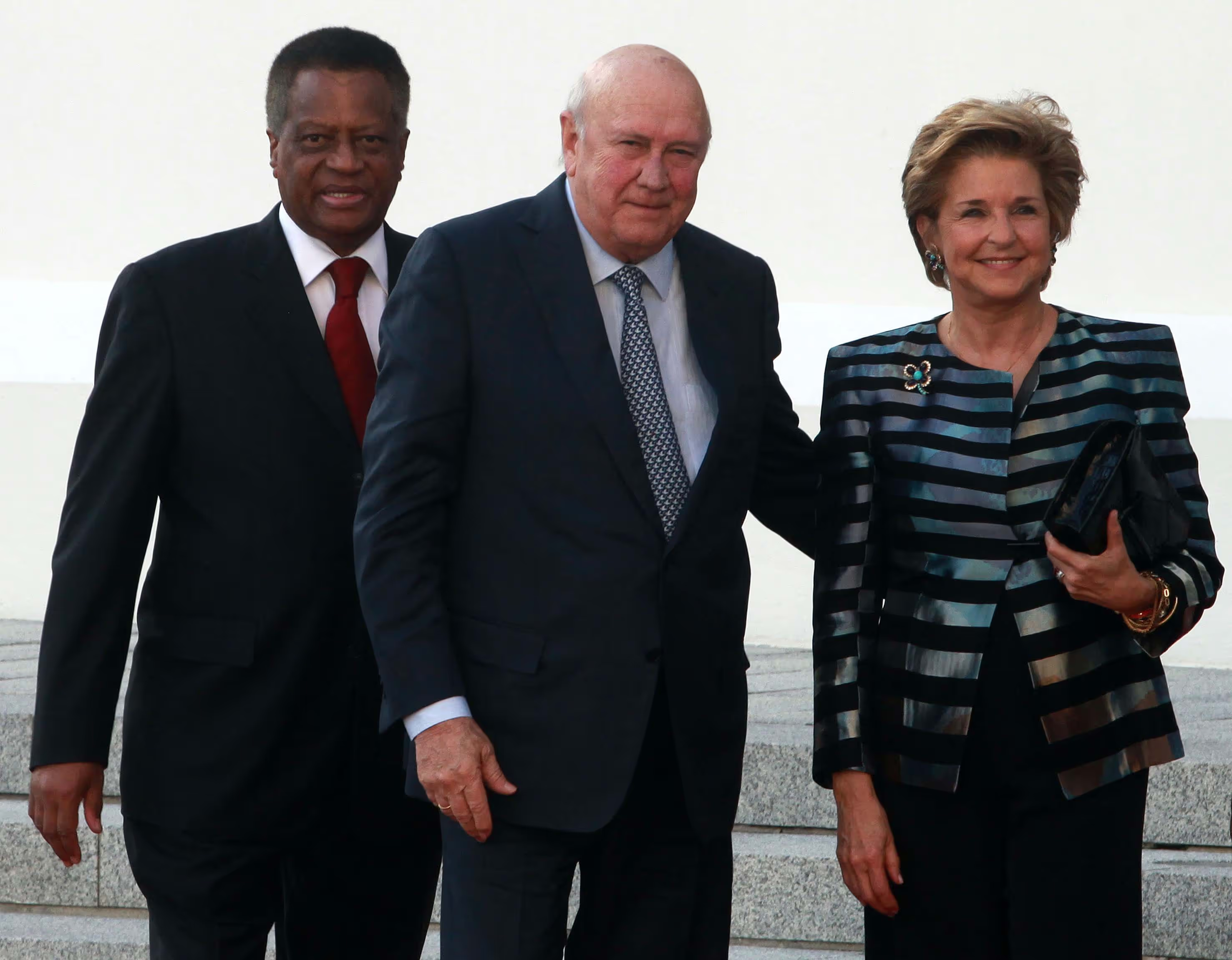

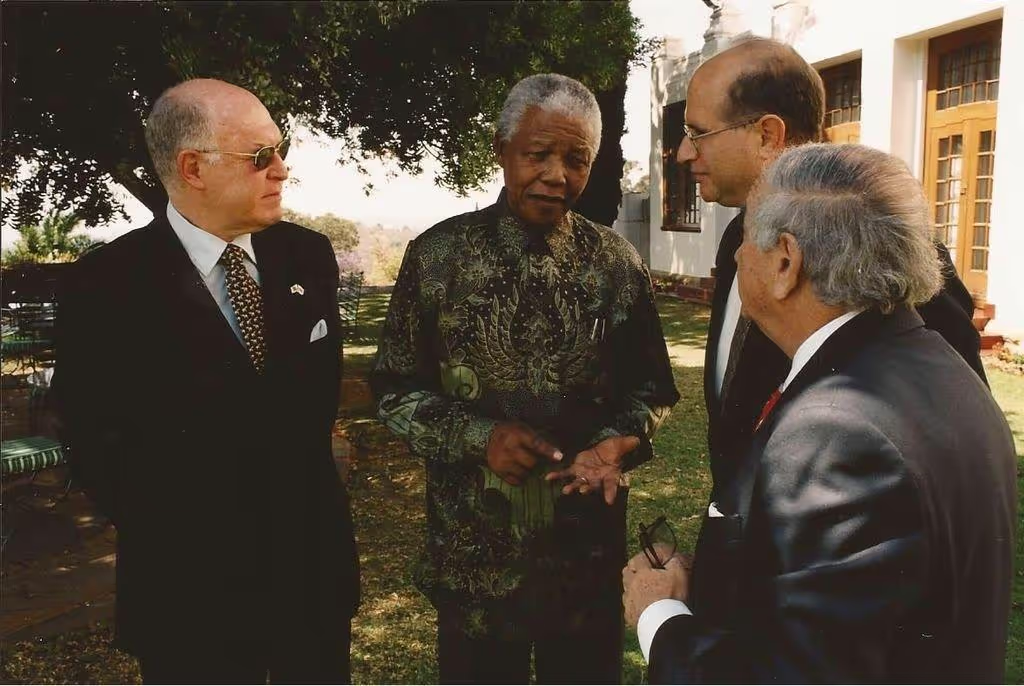

Two decades earlier, in 1994, Nelson Mandela had been inaugurated as the country’s first black president. He’d gripped the hand of FW de Klerk – its last white president – and said in Afrikaans, his former jailers’ language: “Wat is verby, is verby!” (“What is past, is past”). These words had expressed the hope for the country’s transition: that with the right attitudes – repentance from white people and forgiveness from people of colour – the damage that segregation had done could be left in the past.

And some parts of South Africa did look miraculously transformed. Apartheid was the most rigid form of legalised racial segregation history has ever known. Now, on the new high-speed train that connects Johannesburg with its airport, white men stood and yielded their seats to black women who were doing business deals on their iPhones.

But it also felt like a dread was hanging over the country. In one newspaper, I read a letter written by a black South African who warned that the country’s level of dissatisfaction would soon “make the burning of Mississippi” – the unrest in the Jim Crow-era American South – “look like a little bonfire”. And I noticed how much of the past was still present. Many roads were still named after Afrikaner heroes, and mine dumps still divided mostly white-dominated neighbourhoods from the ones black people lived in. But the view from the plane was the most graphic manifestation of this division. From the air, Johannesburg’s dense suburban developments gave way to equestrian estates, then to the folds of the Magaliesberg mountains. And then, beyond the mountains, farmland began. And suddenly I saw it. It was so stark.

Politically, that was always a farce. The homelands had puppet rulers and no local economies; they commanded little loyalty among their so-called citizens. Most of their residents still commuted to white areas to work.

No foreign country ever recognised the demarcation between white and black South Africa as real. And yet over time what began as an absurdist proposition had become real.

As segregation deepened throughout the 20th century, much of the fertile, rain-washed land had been given to white people, while the barren peaks and hot, dry, malaria-ridden lowlands were given to black tribal leaders. From our little plane, the borders between white and black landscapes were clearly visible: green was white South Africa and dust brown was black South Africa. Different patterns of habitation had emerged: in black South Africa, regularly placed little metal-roofed homes dotted the dun-colored earth. White-owned areas were large sweeps of unbroken pasture or cropland

Intensive farming had been a pride and a fixation for white South Africans. The degree to which they made the land yield harvest was supposed to be their justification for keeping it. The apartheid government not only stripped black South Africans of the right to privately buy land, but poured massive amounts of money into assistance programs for white farmers. From the air, the country looked as if a child had cut up travel-magazine pictures of some pastoral English fantasy and spliced them with pictures of the Sahel desert to make a collage.

I was curious to hear from black farmers what it was like to take over formerly white-owned farms. The intense association between whiteness and hi-tech agriculture posed a sharp challenge to black South Africans. Finally able to possess the land they had so long been denied, they felt driven to prove they could farm just as well or better. Land reform was one of the flagship policies that Mandela’s political party, the African National Congress (ANC), instituted after apartheid’s end. It set up a process to buy whites out of their farms and pass them to black people.

The ambitious goal was set to transfer at least 30% of South Africa’s white-owned agricultural land to black people. From 10,000ft up, though, I saw how challenging it would be. When I zoomed in on the lives of the people trying to make it work, I saw that it might be impossible.

Around 2010, the ANC appointed a man named Michael Buys, then in his 40s, to lead land reform in a fruit-producing province in South Africa’s north. I sat down with him in his small, neat office in the provincial capital. When an ad for the job had appeared in the newspaper, Buys recalled feeling a thrill. “I loved the idea of giving land back,” he told me, conspiratorially. “Even of taking it back.

He was about 12, and the government was relocating his parents into a house in a neighbourhood that it was designating “mixed race”, evicting the home’s existing black occupants. Materially, for Buys’s family, this was a win. It was a decent house. But Buys had to stand on a curb and watch as the black couple loaded their possessions on to a military truck. The husband was crying. Even so young, Buys felt it was wrong.

Buys was acutely aware of white-run agriculture’s reputation, and the pressure for black farmers to produce higher yields. Yet he quickly became alarmed by the people coming to apply for previously white-owned farms. “Their business plans were way out there,” he said. The applicants envisioned immediately owning fleets of tractors, with incomes in the millions. “We would say: you are only just starting out! We would explain to them that even white farmers who have tractors and delivery vehicles and [irrigation systems] didn’t get to that level overnight.”

The applicants didn’t accept this, Buys recalled. They would retort: “This is our time. You are a black government. You are our people. You should help us get these things so we can be like the ones for whom we once worked.”

The ANC began by focusing on returning land to those they termed “beneficiaries”: the descendants of black people pushed off land to make way for the mechanised farms. In theory, this was the most direct reparation for the way land was stolen from black people. In practice, it quickly created two huge new problems

The first was that, generations later, there were many more offspring than there had been original victims. And the beneficiaries – who, after a century of industrialisation, now came from diverse lines of work ranging from trucking to mining – had a far greater range of ideas regarding what should be done with the restored land than its original pastoralist occupants had ever had. Groups numbering into the hundreds were resettled on plots that had been owned by a single white family. Many quarreled over its management, sometimes to the death.

The second, more problem was that the descendants of those deprived of rural land were also the least likely to have received the kind of education necessary to run a hi-tech farm in a globalised marketplace. Some couldn’t read; many hadn’t finished high school. Receiving a mechanised farm that immediately demanded the implementation of a computerised marketing plan for exporting the produce to Europe was, for these so-called beneficiaries of liberation, a little like receiving a welcome-to-your-new-country gift basket containing a screaming newborn baby.

Many “beneficiaries” were relatively old and some seemed to have come to the heartbreaking conclusion, after having lived most of their lives condemned to servitude, that servitude was indeed what they had deserved. “We are grateful we got the farm,” Daniel, a former mineworker in his 70s, now the de facto manager of a black-owned lychee plantation, told me when I visited him. Having none of the relevant technical experience, he couldn’t make the farm generate revenue and was now practically starving. “We know we are suffering because we ourselves are not correctly utilising the land.”

Daniel’s land sat in a corridor of fruit plantations that the government bought in the mid-90s and transferred to black people. Twenty years later, the landscape looked as though it had been hit by an apocalyptic event. Lychee and mango trees still grew along the sides of the road, but their leaves were brown and dry, and whatever withered fruit they produced was left on the tree to be gnawed by monkeys. Most of the buildings – sheds, packhouses for drying fruit – had collapsed and been stripped by vandals of their electrical wiring.

Speaking to me sitting on his farmhouse stoop, a threadbare shirt flapping around his thin arms and his hiking boots leaking their stuffing, Daniel told me he thought the missing object standing between him and being a real farmer was a John Deere tractor. If he only had a tractor like the ones he had seen on TV, he could be in business.

“You’re in luck,” I said. I had just come from a farm whose managers wanted to get rid of an unneeded tractor. I said they could drive it over that afternoon. Daniel paused for a long moment and then shook his head sadly. It actually didn’t seem to him it would really solve the problem, he said. Apartheid told black people they simply didn’t have a magic touch necessary to operate a farm, and that notion still operated powerfully.

Buys felt viscerally angry at people like Daniel. But he also knew his anger was a projection of his own shame. Of course many beneficiaries were underskilled. That was what the apartheid regime intended. “I was also embarrassed for myself,” he said. “Because I knew these people’s grandiose fantasies were due to the promises we had been making.”

“We” meant the new government. Just before the 1994 election, the ANC assured South Africans that appropriate housing would be provided to all and there would be “proper” roads and schools. It unveiled an economic policy that promised 500,000 new jobs every year.

A passionate shoutout goes to The Guardian Team!

.png)

Contribute to your future, a Non Profit Organization and buy us a Coffee with 3 simple clicks and a minute of your time. Imagine what we can do together.

To thank you, we will call you personally.

This is the amount that will be distributed amongst the current shareholders.

Current Share Holders

1102/500,000